Changing history¶

The good and bad of history rewriting¶

Why change history?¶

You may be wondering: "Why would I change the history in my repository? Isn't that dangerous? What if I lose information?"

There are in fact a number of cases for which rewriting history is very useful. Many developers don't pay too much attention to structuring their changes while implementing a new feature or fixing a bug. This makes sense: the main focus is the feature or bug, not focusing on getting the history looking just right. Once the feature is complete, a short focused effort is enough to clean up the history. This way, developers can make sure every changeset builds or passes all tests, making bisecting or annotating much easier.

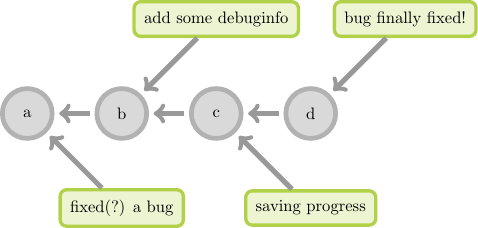

Without such a cleanup, a bugfix might end up looking as follows:

History editing allows you to combine changesets, split them, move them around or delete them from your history. It's extremely powerful and useful, but it can also be dangerous...

Why avoid changing history?¶

You might be thinking: "Well, that sounds amazing! I'll use that all the time!" That's perfectly okay, but history editing isn't without its downsides.

First of all, changing or removing changesets might result in messed up changesets. You might make a mistake that results in a bad changeset. Luckily, Mercurial makes a backup of every changeset that you change or remove. These are stored in a backup bundle in ".hg/strip-backup/". Every time you change history, Mercurial tells you the exact location of the backup.

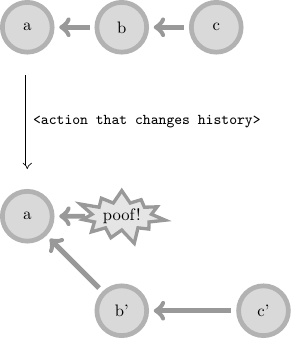

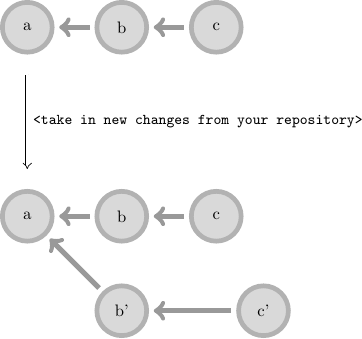

Secondly, changing history is problematic when you do so for changesets that you've published already. Suppose you change a number of changesets as follows:

The above actions get rid of changesets b and c and replace them with b' and c'. However, what if you've already shared the original changesets with other people?

They will see both the old changesets and the new ones! Changing history that you've already shared is considered a bad idea because of the above issue. Every single person who has pulled from your repository, will have to clean up this mess!

To avoid this problem, Mercurial remembers which changesets have already been shared with others and refuses to edit history for those changes.

Adapting the last changeset¶

The easiest and probably one of the most important history editing commands is

hg commit --amend.

This command doesn't create a completely new changeset. Instead, it takes

any new changes in your working directory and combines them with the parent

of the working directory.

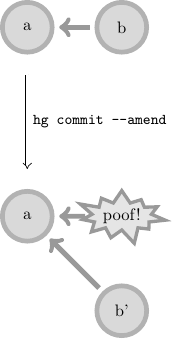

Let's take an example to clarify this. We start out with a repository that has two changesets, a and b:

$ hg log --template "changeset {desc} ({node|short}) changes files: {files}\n"

changeset b (88dd1e15d6c5) changes files: bar

changeset a (33ef7a9bd981) changes files: foo

As we can see, each changeset changes a different file.

What if we made an additional change to our working directory, but we'd like to add it

to our most recent changeset, rather than add a new one? Well, that's no problem...

We can use hg commit --amend:

$ hg status

A woopwoop

$ hg commit --amend -m "b'"

saved backup bundle to $TESTTMP/foo/.hg/strip-backup/88dd1e15d6c5-be2d675b-amend-backup.hg (glob)

$ hg status

$ hg status --change .

A bar

A woopwoop

There are a few interesting things to see here. First of all: it turns out it is possible to change history! We've added a new file to our existing changeset. Secondly, as mentioned before, changing history is safe in Mercurial. A backup bundle is generated when amending and the location of that bundle is shown.

There's actually a small lie above. I mentioned we can add a file to our existing changeset. That's not quite correct: we replaced our original changeset by a new changeset that contains additional changes. This might seem like a small difference, but it has important consequences: the revision hash will be different:

$ hg log --template "changeset {desc} ({node|short}) changes files: {files}\n"

changeset b' (bd2fa2f2c4cc) changes files: bar woopwoop

changeset a (33ef7a9bd981) changes files: foo

We can also show this in a more graphical overview: we start with changesets a and b, but end up with a and b':

Amending is only possible for changesets that are heads (in other words: they don't have children). Other history-editing actions allow much more invasive effects, as we'll see...

Move changesets around in history using rebase¶

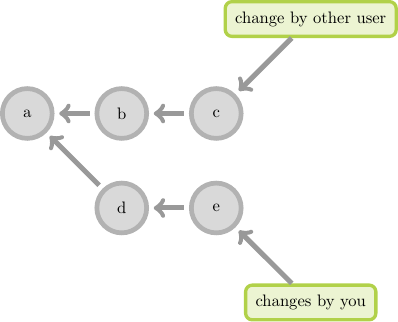

Imagine the following problem: you're working on a project with several people and you'd like to keep the history of your project simple and linear. You'd also like to commit and push regularly. Other people make and push changes, causing the following situation:

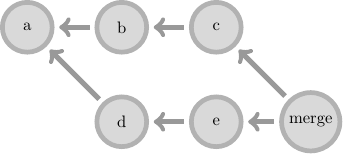

Normally, you'd resolve such a situation by merging your changeset d with the other users changeset c as follows:

One downside to the above way of working is that it makes your history non-linear and complex.

Additionally, it makes commands like hg bisect more difficult to use.

The concept of rebasing provides an alternative.

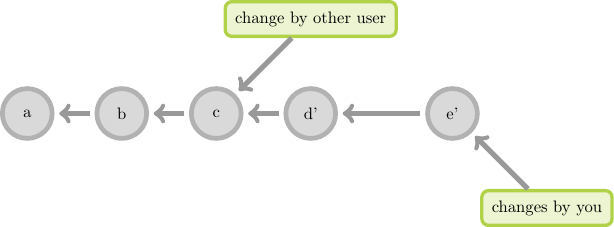

Rebasing allows you to take a bunch of changesets and move them to another part of your history. In the above situation, that would result in cleaner history than using a merge:

As with using hg commit --amend, we also see here that

we end up with new changesets d' and e'.

Note

We're rebasing our changeset on top of the changes the other user made. It's not possible to work the other way around, or we'd be changing public history!

Of course, this looks easy using a graphic representation, but how simple is it to do such a rebase? We'll enable the rebase extension and we can get started:

[extensions]

rebase =

Note

Mercurial provides rebase using an extension because rebase allows changing history. Requiring users to explicitly enable the extension ensures that new users don't shoot themselves in the foot using this powerful feature.

The rebase command always needs a changeset (or multiple) to rebase and a destination on which rebased changesets are created.

You can specify a destination changeset using --dest. Specifying changesets to rebase can be done in several ways, which we can clarify with a few examples.

The first way to specify changesets to rebase is explicitly, using --rev. This way, the exact changesets you mention are rebased:

$ hg log --graph --template "{rev}: {desc}\n"

@ 4: e

|

o 3: d

|

| o 2: c

| |

| o 1: b

|/

o 0: a

$ hg rebase --rev 4 --dest 2

rebasing 4:e302006b2a72 "e" (tip)

saved backup bundle to $TESTTMP/rebaserepo4/.hg/strip-backup/e302006b2a72-19869787-backup.hg (glob)

$ hg log --graph --template "{rev}: {desc}\n"

@ 4: e

|

| o 3: d

| |

o | 2: c

| |

o | 1: b

|/

o 0: a

A second way to specify changesets is to mention the root, using --source. The specified changeset and all of its descendants will be rebased:

$ hg rebase --source 3 --dest 2

rebasing 3:4cfed3aec1ee "d"

rebasing 4:e302006b2a72 "e" (tip)

saved backup bundle to $TESTTMP/rebaserepo2/.hg/strip-backup/4cfed3aec1ee-af238083-backup.hg (glob)

$ hg log --graph --template "{rev}: {desc}\n"

@ 4: e

|

o 3: d

|

o 2: c

|

o 1: b

|

o 0: a

You can also specify a changeset with --base. All of its descendants and ancestors (except those which are also ancestors of the destination) will be rebased:

$ hg rebase --base 4 --dest 2

rebasing 3:4cfed3aec1ee "d"

rebasing 4:e302006b2a72 "e" (tip)

saved backup bundle to $TESTTMP/rebaserepo3/.hg/strip-backup/4cfed3aec1ee-af238083-backup.hg (glob)

$ hg log --graph --template "{rev}: {desc}\n"

@ 4: e

|

o 3: d

|

o 2: c

|

o 1: b

|

o 0: a

Finally, it's possible to execute the hg rebase command without any parameters,

in which case a rebase equivalent to the following is executed:

$ hg rebase --base . --dest "max(branch(.) and not descendants(.))"

In other words, we would rebase the current changeset, along with its ancestors and descendants. This rebase would be done to the last changeset of the current branch that is not a descendant of the current changeset:

$ hg log --graph --template "{rev}: {desc}\n"

o 4: c

|

o 3: b

|

| @ 2: e

| |

| o 1: d

|/

o 0: a

$ hg rebase

rebasing 1:4cfed3aec1ee "d"

rebasing 2:e302006b2a72 "e"

saved backup bundle to $TESTTMP/rebaserepo5/.hg/strip-backup/4cfed3aec1ee-af238083-backup.hg (glob)

To summarize: hg rebase allows you to simplify your history by making it more

linear. That's not the only way to improve history, you can do quite a bit more...

Edit a group of changesets using histedit¶

What can we do so far?

We can change changesets that are heads in our repository by using hg commit --amend.

We can move a group of changesets to a different location in our repository thanks to hg rebase.

Do we need more? One use case we haven't covered yet, is cleaning up a series of changesets.

We might want to remove some changes that shouldn't be pushed, or combine changesets into one

that combines related changes.

Luckily, there's just the command for that: hg histedit.

Just like the rebase command, we can enable histedit through an extension:

[extensions]

histedit =

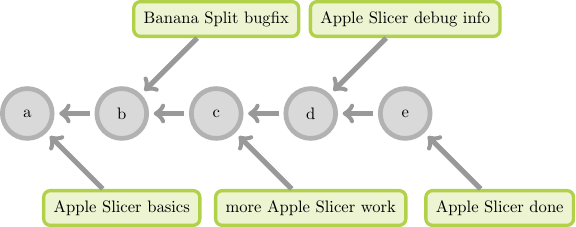

Suppose we've implemented a new feature. It took quite a few iterations, and Mercurial gave us safety by allowing us to commit regularly. Our history now looks as follows:

Even though we've implemented a single new feature (creating a brand-new Apple Slicer), we ended up with quite a few changesets. There's even a bugfix for a different feature inbetween!

Suppose we want to do some more testing on the Apple Slicer (just to make sure it doesn't accidentally slice off our fingers), but the Banana Split bugfix urgently needs to get out the door. What now? How do we handle this situation?

We can simply execute the command hg histedit and our favourite editor

will open up with the histedit interface:

$ hg histedit

pick f680704b6002 0 Apple Slicer basics

pick de4a8ba9ec27 1 Banana Split bugfix

pick 17702bc7efd4 2 more Apple Slicer work

pick 71f1c8ca52a9 3 Apple Slicer debug info

pick 50decf6fef63 4 Apple Slicer done

# Edit history between f680704b6002 and 50decf6fef63

#

# Commits are listed from least to most recent

#

# You can reorder changesets by reordering the lines

#

# Commands:

#

# e, edit = use commit, but stop for amending

# m, mess = edit commit message without changing commit content

# p, pick = use commit

# d, drop = remove commit from history

# f, fold = use commit, but combine it with the one above

# r, roll = like fold, but discard this commit's description and date

#

In our editor, we first see an overview of changesets, with the word pick at the start of the line. This word is actually the default action histedit takes for every changeset. It means that we don't do anything specific with this changeset, we just keep it.

Let's make a change to our history while using nothing else but the pick action! One thing that's possible is to simply reorder changesets in the histedit interface. This will reorder them in the repository history as well.

Since the build for this book requires passing parameters to Mercurial commands

without interaction, we will specify the changesets using a file

and the --commands parameter.

Don't do this yourself, it's much more enjoyable to just call hg histedit.

We'll simply swap a few lines, so we can push our Banana Split bugfix without taking the other changes along.

$ cat histedit-reorder

pick de4a8ba9ec27 1 Banana Split bugfix

pick f680704b6002 0 Apple Slicer basics

pick 17702bc7efd4 2 more Apple Slicer work

pick 71f1c8ca52a9 3 Apple Slicer debug info

pick 50decf6fef63 4 Apple Slicer done

$ hg log -G --template "{node|short}: {desc}\n"

@ 50decf6fef63: Apple Slicer done

|

o 71f1c8ca52a9: Apple Slicer debug info

|

o 17702bc7efd4: more Apple Slicer work

|

o de4a8ba9ec27: Banana Split bugfix

|

o f680704b6002: Apple Slicer basics

$ hg histedit --commands histedit-reorder

saved backup bundle to $TESTTMP/repo/.hg/strip-backup/f680704b6002-38806527-backup.hg (glob)

$ hg log -G --template "{node|short}: {desc}\n"

@ 6b3e1ceeab1c: Apple Slicer done

|

o f9c65ed05c69: Apple Slicer debug info

|

o bfffadb07f49: more Apple Slicer work

|

o 0ea5f1b222af: Apple Slicer basics

|

o 073d4fef87f0: Banana Split bugfix

$ hg push -r 073d4fef87f0 ../publicrepo

pushing to ../publicrepo

searching for changes

adding changesets

adding manifests

adding file changes

added 1 changesets with 1 changes to 1 files

Great! We've moved the urgent bugfix to a different point in our history, which allowed us to push it without having to push parts of a new feature at the same time.

So, what else can we do using histedit?

Let's see what needs to be done:

- We need to remove the extra debug info added while developing our new feature. It was useful during development, but it's no longer needed now.

- Our 'Apple Slicer done' changeset still contains a bug, causing it to output sliced pears when there's a full moon. We should edit that changeset to fix the issue before pushing our feature.

- There's no real need to have changesets with parts of our feature, as it's just a dump of 'changes done so far'. Let's combine all of our changes into one changeset.

By default, when executing hg histedit, all of the changesets

are prefixed with the word pick. This means: take this changeset along,

don't change anything about it.

There's a whole list of other actions available during histedit operations:

- drop: Remove the changeset from your history.

- mess: Change the commit message.

- fold: Combine this changeset with the previous one and show an editor to allow entering a new commit message.

- roll: Like fold, but remove the commit message of this changeset.

- edit: Allow editing the files in this changeset.

We now know what to do, let's give it a try! We'll take the following actions in our histedit operation:

$ cat histedit-change

pick 0ea5f1b222af 0 Apple Slicer basics

fold bfffadb07f49 1 more Apple Slicer work

drop f9c65ed05c69 2 Apple Slicer debug info

fold 6b3e1ceeab1c 3 Apple Slicer done

In other words, we'll fold all our changes together, except for the debugging info (which we'll omit).

Your editor will pop up and allow you to change the commit messages while running histedit. That's not really an option in this book, so we'll just show you the overview of everything that happens while running the command:

$ hg histedit --commands histedit-change

Apple Slicer basics

***

more Apple Slicer work

HG: Enter commit message. Lines beginning with 'HG:' are removed.

HG: Leave message empty to abort commit.

HG: --

HG: user: test

HG: branch 'default'

HG: added appleslicer

Apple Slicer basics

***

more Apple Slicer work

***

Apple Slicer done

HG: Enter commit message. Lines beginning with 'HG:' are removed.

HG: Leave message empty to abort commit.

HG: --

HG: user: test

HG: branch 'default'

HG: added appleslicer

saved backup bundle to $TESTTMP/repo/.hg/strip-backup/ca4523aafc9c-8cf333b6-backup.hg (glob)

saved backup bundle to $TESTTMP/repo/.hg/strip-backup/e71e82a798fe-750904b9-backup.hg (glob)

saved backup bundle to $TESTTMP/repo/.hg/strip-backup/0ea5f1b222af-fb81c5af-backup.hg (glob)

We can see several editor texts popping up above, progressively combinging commit messages. In the end, we only have a single Apple Slicer changeset left:

$ hg log -G --template "{node|short}: {desc}\n"

@ 9cb38cc13fd6: Apple Slicer basics

| ***

| more Apple Slicer work

| ***

| Apple Slicer done

o 073d4fef87f0: Banana Split bugfix

You may have noticed that, unlike with rebase, we never specified a set of revisions to modify. By default, histedit will edit the ancestors of the current changeset that have not been shared with anyone yet.

You can override this in two ways:

By specifying a revision explicitly:

$ hg histedit -r ANCESTORREVISION

By using the parameter --outgoing. This parameter allows you to select the first changeset not yet included in the destination repository:

$ hg histedit --outgoing

Just like with rebase and amend, Mercurial will not allow you to change public changesets using hg histedit.

Safely changing history¶

How exactly does Mercurial manage to keep you from getting in trouble while changing history?

Mercurial actually keeps track of something called phases. Every time you push changesets to another repository, Mercurial analyses the phases for those changesets and adapts them if necessary.

There are three phases, each resulting in different behaviour:

- secret: This phase indicates that a changeset should not be shared with others. If someone else pulls from your repository, or you push to another repository, these changesets will not be pushed along.

- draft: This is the default phase for any new changeset you create. It indicates that the changeset has not yet been pushed to another repository. Pushing this changeset to another repository will change its phase to public.

- public: This phase indicates that a changeset was already shared with others. This means changing history should not be allowed if it includes this changeset.

Mercurial uses this information to determine which changesets are allowed to be changed. It also determines how to select changes to rebase or histedit automatically. For example: using histedit without any arguments will only show draft and secret changesets for you to change.

Overriding default behaviour¶

There are two ways to explicitly change the behaviour of phases, either in a repository, or when communicating with another repository.

In a repository, it's possible to explicitly change the phase of certain changesets

using the appropriate hg phase command. You can, for example, change

the phase from draft to public:

$ hg phase -r .

1: draft

$ hg phase -r . -p

$ hg phase -r .

1: public

As you can see, you can also use the hg phase command to view phases,

rather than change them.

Secret is considered the highest phase, followed by draft and finally public. Moving phases from a higher phase to a lower phase is allowed by default, moving phases from a lower to a higher phase is not. Think of it like water: it moves down the mountain, not up the mountain.

Of course, it's possible to take a bottle of water up the mountain, but that's more difficult. Similarly, you can also force a phase change in the other direction:

$ hg phase -r .

1: public

$ hg phase -r . -d

cannot move 1 changesets to a higher phase, use --force

no phases changed

$ hg phase -r .

1: public

$ hg phase -r . -d --force

$ hg phase -r .

1: draft

In normal circumstance, you should never change phases yourself. They will automatically change when you push to other repositories.

Of course, you may have a situation where you have several repositories you want to push to, without having finished your changesets. There are several use cases that can result in this situation, just a few are:

- Pushing your changes to another repository of your own, for example for backup purposes or to be able to test your changes on a different machine.

- Pushing your changes to a staging server, where they are validated and only become public if the validation was successful.

Luckily, it's possible to handle this situation in Mercurial. By default, all Mercurial repositories are publishing. This means, as soon as you push to them, all the changesets that you push will become public.

You can configure the target repository so pushing to it will not change draft changesets to public:

[phases]

publish = False

Conclusion¶

There are several ways to change history in Mercurial, each with its own use case, benefits and downsides.

Mercurial additionally supports you by preventing you from changing history that you've already shared with others.

As a result, history editing in Mercurial is safe yet powerful.