Merging changes¶

We've now covered cloning a repository, making changes in a repository, and pulling or pushing changes from one repository into another. Working together not only requires us to send around changes, we also need to be able to combine or merge those changes.

Merging streams of work¶

Merging is a fundamental part of working with a distributed revision control tool. Here are a few cases in which the need to merge work arises.

- Alice and Bob each have a personal copy of a repository for a project they're collaborating on. Alice fixes a bug in her repository; Bob adds a new feature in his. They want the shared repository to contain both the bug fix and the new feature.

- Cynthia frequently works on several different tasks for a single project at once, each safely isolated in its own repository. Working this way means that she often needs to merge one piece of her own work with another.

Because we need to merge often, Mercurial makes the process easy. Let's walk through a merge. We'll begin by cloning yet another repository (see how often they spring up?) and making a change in it.

$ hg clone hello my-new-hello

updating to branch default

2 files updated, 0 files merged, 0 files removed, 0 files unresolved

$ cd my-new-hello

$ # Make some simple edits to hello.c.

$ ../my-text-editor hello.c

$ hg commit -m 'A new hello for a new day.'

We should now have two copies of hello.c with different contents. The histories of the two repositories have also diverged, as illustrated in

fig:tour-merge:sep-repos. Here is a copy of our file from one repository.

$ cat hello.c

/*

* Placed in the public domain by Bryan O'Sullivan. This program is

* not covered by patents in the United States or other countries.

*/

#include <stdio.h>

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

printf("once more, hello.\n");

printf("hello, world!\");

printf("hello again!\n");

return 0;

}

And here is our slightly different version from the other repository.

$ cat ../my-hello/hello.c

/*

* Placed in the public domain by Bryan O'Sullivan. This program is

* not covered by patents in the United States or other countries.

*/

#include <stdio.h>

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

printf("hello, world!\");

printf("hello again!\n");

return 0;

}

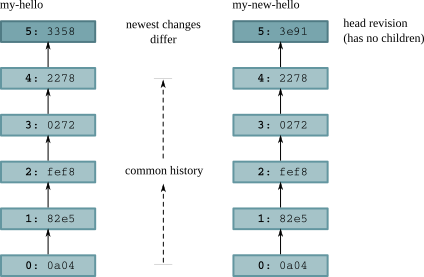

Divergent recent histories of the my-hello and my-new-hello repositories

We already know that pulling changes from our my-hello repository will have no effect on the working directory.

$ hg pull ../my-hello

pulling from ../my-hello

searching for changes

adding changesets

adding manifests

adding file changes

added 1 changesets with 1 changes to 1 files (+1 heads)

(run 'hg heads' to see heads, 'hg merge' to merge)

However, the hg pull command says something about “heads”.

Head changesets¶

Remember that Mercurial records what the parent of each changeset is. If a changeset has a parent, we call it a child or descendant of the parent. A head is a changeset that has no children. The tip revision is thus a head, because the newest revision in a repository doesn't have any children. There are times when a repository can contain more than one head.

Repository contents after pulling from my-hello into my-new-hello

In fig:tour-merge:pull, you can see the effect of the pull from my-hello into my-new-hello. The history that was already present in

my-new-hello is untouched, but a new revision has been added. By referring to fig:tour-merge:sep-repos, we can see that the changeset ID

remains the same in the new repository, but the revision number has changed. (This, incidentally, is a fine example of why it's not safe to use

revision numbers when discussing changesets.) We can view the heads in a repository using the hg heads command.

$ hg heads

changeset: 6:3358452fd7d5

tag: tip

parent: 4:2278160e78d4

user: test

date: Thu Jan 01 00:00:00 1970 +0000

summary: Added an extra line of output

changeset: 5:3e917d898551

user: test

date: Thu Jan 01 00:00:00 1970 +0000

summary: A new hello for a new day.

Performing the merge¶

What happens if we try to use the normal hg update command to update to the new tip?

$ hg update

0 files updated, 0 files merged, 0 files removed, 0 files unresolved

1 other heads for branch "default"

Mercurial is telling us that the hg update command keeps us on the same head (no files have been changed).

It informs us of the other head, but it won't do the merge itself, unless we force it do so.

(Incidentally, forcing an update to the other head with hg update -C would revert any uncommitted changes in the working directory.)

To start a merge between the two heads, we use the hg merge command.

$ hg merge

merging hello.c

0 files updated, 1 files merged, 0 files removed, 0 files unresolved

(branch merge, don't forget to commit)

We resolve the contents of hello.c This updates the working directory so that it contains changes from both heads, which is reflected in both

the output of hg parents and the contents of hello.c.

$ hg parents

changeset: 5:3e917d898551

user: test

date: Thu Jan 01 00:00:00 1970 +0000

summary: A new hello for a new day.

changeset: 6:3358452fd7d5

tag: tip

parent: 4:2278160e78d4

user: test

date: Thu Jan 01 00:00:00 1970 +0000

summary: Added an extra line of output

$ cat hello.c

/*

* Placed in the public domain by Bryan O'Sullivan. This program is

* not covered by patents in the United States or other countries.

*/

#include <stdio.h>

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

printf("once more, hello.\n");

printf("hello, world!\");

printf("hello again!\n");

return 0;

}

Committing the results of the merge¶

Once we've started a merge, hg parents will display two parents until we hg commit the results of the merge.

$ hg commit -m 'Merged changes'

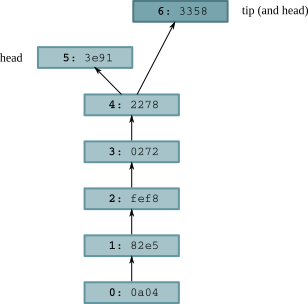

We now have a new tip revision; notice that it has both of our former heads as its parents. These are the same revisions that were previously

displayed by hg parents.

$ hg tip

changeset: 7:e83c60091e12

tag: tip

parent: 5:3e917d898551

parent: 6:3358452fd7d5

user: test

date: Thu Jan 01 00:00:00 1970 +0000

summary: Merged changes

In fig:tour-merge:merge, you can see a representation of what happens to the working directory during the merge, and how this affects the repository when the commit happens. During the merge, the working directory has two parent changesets, and these become the parents of the new changeset.

Working directory and repository during merge, and following commit

We sometimes talk about a merge having sides: the left side is the first parent in the output of hg parents, and the right side is the second.

If the working directory was at e.g. revision 5 before we began a merge, that revision will become the left side of the merge.

Merging conflicting changes¶

Most merges are simple affairs, but sometimes you'll find yourself merging changes where each side modifies the same portions of the same files. Unless both modifications are identical, this results in a conflict, where you have to decide how to reconcile the different changes into something coherent.

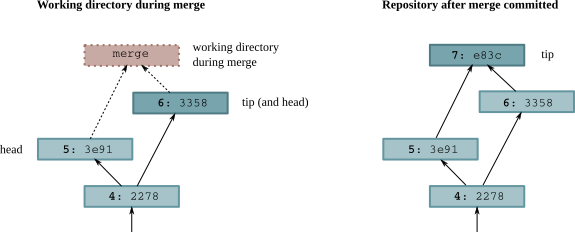

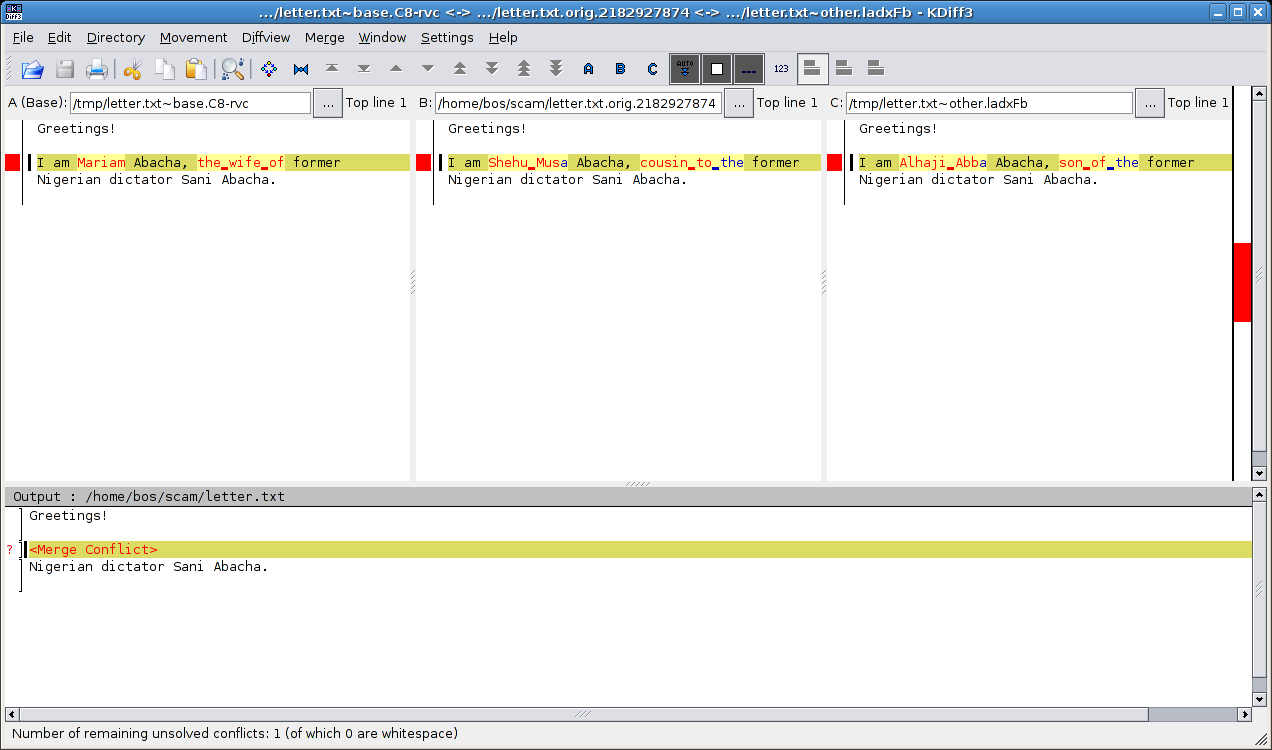

Conflicting changes to a document

fig:tour-merge:conflict illustrates an instance of two conflicting changes to a document. We started with a single version of the file; then we made some changes; while someone else made different changes to the same text. Our task in resolving the conflicting changes is to decide what the file should look like.

Mercurial doesn't have a built-in facility for handling conflicts. Instead, it runs an external program, usually one that displays some kind of graphical conflict resolution interface. By default, Mercurial tries to find one of several different merging tools that are likely to be installed on your system. It first tries a few fully automatic merging tools; if these don't succeed (because the resolution process requires human guidance) or aren't present, it tries a few different graphical merging tools.

It's also possible to get Mercurial to run a specific program or script, by setting the HGMERGE environment variable to the name of your preferred program.

Using a graphical merge tool¶

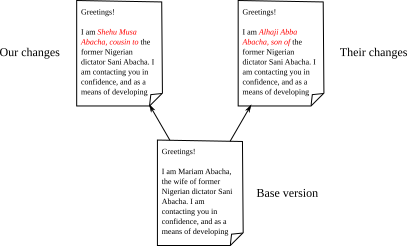

My preferred graphical merge tool is kdiff3, which I'll use to describe the features that are common to graphical file merging tools. You can see

a screenshot of kdiff3 in action in fig:tour-merge:kdiff3. The kind of merge it is performing is called a three-way merge, because there

are three different versions of the file of interest to us. The tool thus splits the upper portion of the window into three panes:

- At the left is the base version of the file, i.e. the most recent version from which the two versions we're trying to merge are descended.

- In the middle is “our” version of the file, with the contents that we modified.

- On the right is “their” version of the file, the one that from the changeset that we're trying to merge with.

In the pane below these is the current result of the merge. Our task is to replace all of the red text, which indicates unresolved conflicts, with some sensible merger of the “ours” and “theirs” versions of the file.

All four of these panes are locked together; if we scroll vertically or horizontally in any of them, the others are updated to display the corresponding sections of their respective files.

Using kdiff3 to merge versions of a file

For each conflicting portion of the file, we can choose to resolve the conflict using some combination of text from the base version, ours, or theirs. We can also manually edit the merged file at any time, in case we need to make further modifications.

There are many file merging tools available, too many to cover here. They vary in which platforms they are available for, and in their particular strengths and weaknesses. Most are tuned for merging files containing plain text, while a few are aimed at specialised file formats (generally XML).

A worked example¶

In this example, we will reproduce the file modification history of fig:tour-merge:conflict above. Let's begin by creating a repository with a base version of our document.

$ cat > letter.txt <<EOF

> Greetings!

>

> I am Mariam Abacha, the wife of former

> Nigerian dictator Sani Abacha.

> EOF

$ hg add letter.txt

$ hg commit -m '419 scam, first draft'

We'll clone the repository and make a change to the file.

$ cd ..

$ hg clone scam scam-cousin

updating to branch default

1 files updated, 0 files merged, 0 files removed, 0 files unresolved

$ cd scam-cousin

$ cat > letter.txt <<EOF

> Greetings!

>

> I am Shehu Musa Abacha, cousin to the former

> Nigerian dictator Sani Abacha.

> EOF

$ hg commit -m '419 scam, with cousin'

And another clone, to simulate someone else making a change to the file. (This hints at the idea that it's not all that unusual to merge with yourself when you isolate tasks in separate repositories, and indeed to find and resolve conflicts while doing so.)

$ cd ..

$ hg clone scam scam-son

updating to branch default

1 files updated, 0 files merged, 0 files removed, 0 files unresolved

$ cd scam-son

$ cat > letter.txt <<EOF

> Greetings!

>

> I am Alhaji Abba Abacha, son of the former

> Nigerian dictator Sani Abacha.

> EOF

$ hg commit -m '419 scam, with son'

Having created two different versions of the file, we'll set up an environment suitable for running our merge.

$ cd ..

$ hg clone scam-cousin scam-merge

updating to branch default

1 files updated, 0 files merged, 0 files removed, 0 files unresolved

$ cd scam-merge

$ hg pull -u ../scam-son

pulling from ../scam-son

searching for changes

adding changesets

adding manifests

adding file changes

added 1 changesets with 1 changes to 1 files (+1 heads)

0 files updated, 0 files merged, 0 files removed, 0 files unresolved

1 other heads for branch "default"

In this example, I'll set HGMERGE to tell Mercurial to use the non-interactive merge command. This is bundled with many Unix-like systems. (If

you're following this example on your computer, don't bother setting HGMERGE. You'll get dropped into a GUI file merge tool instead, which is much

preferable.)

$ export HGMERGE=merge

$ hg merge

merging letter.txt

merge: warning: conflicts during merge

merging letter.txt failed!

0 files updated, 0 files merged, 0 files removed, 1 files unresolved

use 'hg resolve' to retry unresolved file merges or 'hg update -C .' to abandon

$ cat letter.txt

Greetings!

<<<<<<< $TESTTMP/scam-merge/letter.txt

I am Shehu Musa Abacha, cousin to the former

=======

I am Alhaji Abba Abacha, son of the former

>>>>>>> /tmp/letter~other.6Nt30p.txt

Nigerian dictator Sani Abacha.

Because merge can't resolve the conflicting changes, it leaves merge markers inside the file that has conflicts, indicating which lines have

conflicts, and whether they came from our version of the file or theirs.

Mercurial can tell from the way merge exits that it wasn't able to merge successfully, so it tells us what commands we'll need to run if we want

to redo the merge operation. This could be useful if, for example, we were running a graphical merge tool and quit because we were confused or

realised we had made a mistake.

If automatic or manual merges fail, there's nothing to prevent us from “fixing up” the affected files ourselves, and committing the results of our merge:

$ cat > letter.txt <<EOF

> Greetings!

>

> I am Bryan O'Sullivan, no relation of the former

> Nigerian dictator Sani Abacha.

> EOF

$ hg resolve -m letter.txt

(no more unresolved files)

$ hg commit -m 'Send me your money'

$ hg tip

changeset: 3:e20534b499a5

tag: tip

parent: 1:a0e7852f5ec3

parent: 2:ab1c889d95a4

user: test

date: Thu Jan 01 00:00:00 1970 +0000

summary: Send me your money

Simplifying the pull-merge-commit sequence¶

The process of merging changes as outlined above is straightforward, but requires running three commands in sequence.

hg pull -u

hg merge

hg commit -m 'Merged remote changes'

In the case of the final commit, you also need to enter a commit message, which is almost always going to be a piece of uninteresting “boilerplate” text.

It would be nice to reduce the number of steps needed, if this were possible. Indeed, Mercurial is distributed with an extension called fetch that

does just this.

Mercurial provides a flexible extension mechanism that lets people extend its functionality, while keeping the core of Mercurial small and easy to deal with. Some extensions add new commands that you can use from the command line, while others work “behind the scenes,” for example adding capabilities to Mercurial's built-in server mode.

The fetch extension adds a new command called, not surprisingly, hg fetch. This extension acts as a combination of hg pull -u,

hg merge and hg commit. It begins by pulling changes from another repository into the current repository. If it finds that the changes added a

new head to the repository, it updates to the new head, begins a merge, then (if the merge succeeded) commits the result of the merge with an

automatically-generated commit message. If no new heads were added, it updates the working directory to the new tip changeset.

Enabling the fetch extension is easy. Edit the .hgrc file in your home directory, and either go to the extensions section or create an

extensions section. Then add a line that simply reads “fetch=”.

[extensions]

fetch =

(Normally, the right-hand side of the “=” would indicate where to find the extension, but since the fetch extension is in the standard

distribution, Mercurial knows where to find it.)

Renaming, copying, and merging¶

During the life of a project, we will often want to change the layout of its files and directories. This can be as simple as renaming a single file, or as complex as restructuring the entire hierarchy of files within the project.

Mercurial supports these kinds of complex changes fluently, provided we tell it what we're doing. If we want to rename a file, we should use the

hg rename [1] command to rename it, so that Mercurial can do the right thing later when we merge.

| [1] | If you're a Unix user, you'll be glad to know that the hg rename command can be abbreviated as hg mv. |

The results of copying during a merge¶

What happens during a merge is that changes “follow” a copy. To best illustrate what this means, let's create an example. We'll start with the usual tiny repository that contains a single file.

$ hg init my-copy

$ cd my-copy

$ echo line > file

$ hg add file

$ hg commit -m 'Added a file'

We need to do some work in parallel, so that we'll have something to merge. So let's clone our repository.

$ cd ..

$ hg clone my-copy your-copy

updating to branch default

1 files updated, 0 files merged, 0 files removed, 0 files unresolved

Back in our initial repository, let's use the hg copy command to make a copy of the first file we created.

$ cd my-copy

$ hg copy file new-file

If we look at the output of the hg status command afterwards, the copied file looks just like a normal added file.

$ hg status

A new-file

But if we pass the -C option to hg status, it prints another line of output: this is the file that our newly-added file was copied from.

$ hg status -C

A new-file

file

$ hg commit -m 'Copied file'

Now, back in the repository we cloned, let's make a change in parallel. We'll add a line of content to the original file that we created.

$ cd ../your-copy

$ echo 'new contents' >> file

$ hg commit -m 'Changed file'

Now we have a modified file in this repository. When we pull the changes from the first repository, and merge the two heads, Mercurial will

propagate the changes that we made locally to file into its copy, new-file.

$ hg pull ../my-copy

pulling from ../my-copy

searching for changes

adding changesets

adding manifests

adding file changes

added 1 changesets with 1 changes to 1 files (+1 heads)

(run 'hg heads' to see heads, 'hg merge' to merge)

$ hg merge

merging file and new-file to new-file

0 files updated, 1 files merged, 0 files removed, 0 files unresolved

(branch merge, don't forget to commit)

$ cat new-file

line

new contents

Why should changes follow copies?¶

This behavior—of changes to a file propagating out to copies of the file—might seem esoteric, but in most cases it's highly desirable.

First of all, remember that this propagation only happens when you merge. So if you hg copy a file, and subsequently modify the original file

during the normal course of your work, nothing will happen.

The second thing to know is that modifications will only propagate across a copy as long as the changeset that you're merging changes from hasn't yet seen the copy.

The reason that Mercurial does this is as follows. Let's say I make an important bug fix in a source file, and commit my changes. Meanwhile, you've

decided to hg copy the file in your repository, without knowing about the bug or having seen the fix, and you have started hacking on your copy of

the file.

If you pulled and merged my changes, and Mercurial didn't propagate changes across copies, your new source file would now contain the bug, and unless you knew to propagate the bug fix by hand, the bug would remain in your copy of the file.

By automatically propagating the change that fixed the bug from the original file to the copy, Mercurial prevents this class of problem. To my knowledge, Mercurial is the only revision control system that propagates changes across copies like this.

Once your change history has a record that the copy and subsequent merge occurred, there's usually no further need to propagate changes from the original file to the copied file, and that's why Mercurial only propagates changes across copies at the first merge, and not afterwards.

How to make changes not follow a copy¶

If, for some reason, you decide that this business of automatically propagating changes across copies is not for you, simply use your system's normal

file copy command (on Unix-like systems, that's cp) to make a copy of a file, then hg add the new copy by hand. Before you do so, though,

please do reread sec:daily:why-copy, and make an informed decision that this behavior is not appropriate to your specific case.

Renaming files and merging changes¶

Since Mercurial's rename is implemented as copy-and-remove, the same propagation of changes happens when you merge after a rename as after a copy.

If I modify a file, and you rename it to a new name, and then we merge our respective changes, my modifications to the file under its original name will be propagated into the file under its new name. (This is something you might expect to “simply work,” but not all revision control systems actually do this.)

Whereas having changes follow a copy is a feature where you can perhaps nod and say “yes, that might be useful,” it should be clear that having them follow a rename is definitely important. Without this facility, it would simply be too easy for changes to become orphaned when files are renamed.

Divergent renames and merging¶

The case of diverging names occurs when two developers start with a file—let's call it foo—in their respective repositories.

$ hg clone orig anne

updating to branch default

1 files updated, 0 files merged, 0 files removed, 0 files unresolved

$ hg clone orig bob

updating to branch default

1 files updated, 0 files merged, 0 files removed, 0 files unresolved

Anne renames the file to bar.

$ cd anne

$ hg rename foo bar

$ hg ci -m 'Rename foo to bar'

Meanwhile, Bob renames it to quux. (Remember that hg mv is an alias for hg rename.)

$ cd ../bob

$ hg mv foo quux

$ hg ci -m 'Rename foo to quux'

I like to think of this as a conflict because each developer has expressed different intentions about what the file ought to be named.

What do you think should happen when they merge their work? Mercurial's actual behavior is that it always preserves both names when it merges changesets that contain divergent renames.

# See https://bz.mercurial-scm.org/show_bug.cgi?id=455

$ cd ../orig

$ hg pull -u ../anne

pulling from ../anne

searching for changes

adding changesets

adding manifests

adding file changes

added 1 changesets with 1 changes to 1 files

1 files updated, 0 files merged, 1 files removed, 0 files unresolved

$ hg pull ../bob

pulling from ../bob

searching for changes

adding changesets

adding manifests

adding file changes

added 1 changesets with 1 changes to 1 files (+1 heads)

(run 'hg heads' to see heads, 'hg merge' to merge)

$ hg merge

note: possible conflict - foo was renamed multiple times to:

bar

quux

1 files updated, 0 files merged, 0 files removed, 0 files unresolved

(branch merge, don't forget to commit)

$ ls

bar

quux

Notice that while Mercurial warns about the divergent renames, it leaves it up to you to do something about the divergence after the merge.

Convergent renames and merging¶

Another kind of rename conflict occurs when two people choose to rename different source files to the same destination. In this case, Mercurial runs its normal merge machinery, and lets you guide it to a suitable resolution.

Dealing with tricky merges¶

In a complicated or large project, it's not unusual for a merge of two changesets to result in some headaches. Suppose there's a big source file that's been extensively edited by each side of a merge: this is almost inevitably going to result in conflicts, some of which can take a few tries to sort out.

Let's develop a simple case of this and see how to deal with it. We'll start off with a repository containing one file, and clone it twice.

$ hg init conflict

$ cd conflict

$ echo first > myfile.txt

$ hg ci -A -m first

adding myfile.txt

$ cd ..

$ hg clone conflict left

updating to branch default

1 files updated, 0 files merged, 0 files removed, 0 files unresolved

$ hg clone conflict right

updating to branch default

1 files updated, 0 files merged, 0 files removed, 0 files unresolved

In one clone, we'll modify the file in one way.

$ cd left

$ echo left >> myfile.txt

$ hg ci -m left

In another, we'll modify the file differently.

$ cd ../right

$ echo right >> myfile.txt

$ hg ci -m right

Next, we'll pull each set of changes into our original repo.

$ cd ../conflict

$ hg pull -u ../left

pulling from ../left

searching for changes

adding changesets

adding manifests

adding file changes

added 1 changesets with 1 changes to 1 files

1 files updated, 0 files merged, 0 files removed, 0 files unresolved

$ hg pull -u ../right

pulling from ../right

searching for changes

adding changesets

adding manifests

adding file changes

added 1 changesets with 1 changes to 1 files (+1 heads)

0 files updated, 0 files merged, 0 files removed, 0 files unresolved

1 other heads for branch "default"

We expect our repository to now contain two heads.

$ hg heads

changeset: 2:a285bd614825

tag: tip

parent: 0:c68e9ce15931

user: test

date: Thu Jan 01 00:00:00 1970 +0000

summary: right

changeset: 1:b7ac2e78b85a

user: test

date: Thu Jan 01 00:00:00 1970 +0000

summary: left

Normally, if we run hg merge at this point, it will drop us into a GUI that will let us manually resolve the conflicting edits to myfile.txt. However, to simplify

things for presentation here, we'd like the merge to fail immediately instead. Here's one way we can do so.

$ export HGMERGE=false

We've told Mercurial's merge machinery to run the command false (which, as we desire, fails immediately) if it detects a merge that it can't sort

out automatically.

If we now fire up hg merge, it should grind to a halt and report a failure.

$ hg merge

merging myfile.txt

merging myfile.txt failed!

0 files updated, 0 files merged, 0 files removed, 1 files unresolved

use 'hg resolve' to retry unresolved file merges or 'hg update -C .' to abandon

Even if we don't notice that the merge failed, Mercurial will prevent us from accidentally committing the result of a failed merge.

$ hg commit -m 'Attempt to commit a failed merge'

abort: unresolved merge conflicts (see 'hg help resolve')

When hg commit fails in this case, it suggests that we use the unfamiliar hg resolve command. As usual, hg help resolve will print a

helpful synopsis.

File resolution states¶

When a merge occurs, most files will usually remain unmodified. For each file where Mercurial has to do something, it tracks the state of the file.

- A resolved file has been successfully merged, either automatically by Mercurial or manually with human intervention.

- An unresolved file was not merged successfully, and needs more attention.

If Mercurial sees any file in the unresolved state after a merge, it considers the merge to have failed. Fortunately, we do not need to restart the entire merge from scratch.

The --list or -l option to hg resolve prints out the state of each merged file.

$ hg resolve -l

U myfile.txt

In the output from hg resolve, a resolved file is marked with R, while an unresolved file is marked with U. If any files are listed with U, we know that

an attempt to commit the results of the merge will fail.

Resolving a file merge¶

We have several options to move a file from the unresolved into the resolved state. By far the most common is to rerun hg resolve. If we pass the

names of individual files or directories, it will retry the merges of any unresolved files present in those locations. We can also pass the --all

or -a option, which will retry the merges of all unresolved files.

Mercurial also lets us modify the resolution state of a file directly. We can manually mark a file as resolved using the --mark option, or as

unresolved using the --unmark option. This allows us to clean up a particularly messy merge by hand, and to keep track of our progress with each

file as we go.