A tour of Mercurial: the basics¶

Installing Mercurial on your system¶

Prebuilt binary packages of Mercurial are available for every popular operating system from the Mercurial website at https://www.mercurial-scm.org. These make it easy to start using Mercurial on your computer immediately. Additionally, specifically for Linux, your package manager should include the possibility to install Mercurial.

Tortoisehg¶

One of the most popular front-ends for Mercurial is TortoiseHg. It provides a very nice graphical interface for Mercurial, but also allows you to access the command line interface. TortoiseHg can be found at http://tortoisehg.bitbucket.org/ and is available for Windows, Mac OS X and Linux.

Atlassian SourceTree¶

Another popular Mercurial front-end is Atlassian SourceTree, which provides a nice graphical interface and can be freely downloaded from https://www.sourcetreeapp.com/. Atlassian SourceTree is available for Windows and Mac OS X.

Other choices¶

The above only gives an overview of the most popular graphical interfaces for Mercurial. There are more such applications, and many editors, IDE's, review tools, continuous integration tools... have Mercurial integration as well. You can find an overview of these on the Mercurial wiki at https://www.mercurial-scm.org/wiki/OtherTools.

Basic configuration¶

Mercurial requires very little configuration. You can run quite a few commands without configuring anything. However, you need to configure at least your username if you wish to contribute yourself to a project that uses Mercurial.

Mercurial has a number of ways to determine your username. The advised way for most users is through a file in your home directory called .hgrc,

with a username entry, that will be used next. To see what the contents of this file should look like, refer to sec:tour-basic:username.

Mercurial checks quite a few additional locations to determine what username to use.

- If you specify a

-uor--useroption to Mercurial commands that need a username, this will be used with highest priority. - If you have set the HGUSER environment variable, this is checked next.

- The above mentioned

.hgrcfile is next to be checked. - If you have set the EMAIL environment variable, this will be used next.

- Mercurial will query your system to find out your local user name and host name, and construct a username from these components. Since this often results in a username that is not very useful, it will print a warning if it has to do this.

If all of these mechanisms fail, Mercurial will fail, printing an error message. In this case, it will not let you commit until you set up a username.

You should think of the HGUSER environment variable and the -u option as ways to override Mercurial's default selection of username. For normal

use, the simplest and most robust way to set a username for yourself is by creating a .hgrc file; see below for details.

Creating a Mercurial configuration file¶

To set a user name, use your favorite editor to create a file called .hgrc in your home directory. Mercurial will use this file to look up your

personalised configuration settings. The initial contents of your .hgrc should look like this.

# This is a Mercurial configuration file.

[ui]

username = Firstname Lastname <email.address@example.net>

The “[ui]” line begins a section of the config file, so you can read the “username = ...” line as meaning “set the value of the username

item in the ui section”. A section continues until a new section begins, or the end of the file. Mercurial ignores empty lines and treats any text

from “#” to the end of a line as a comment.

Tip

When we refer to your home directory, on an English language installation of Windows this will usually be a folder named after your user name in

C:\Documents and Settings. You can find out the exact name of your home directory by opening a command prompt window and running the following

command.

C:\\> echo %UserProfile%

Choosing a user name¶

You can use any text you like as the value of the username config item, since this information is for reading by other people, but will not be

interpreted by Mercurial. The convention that most people follow is to use their name and email address, as in the example above.

Note

Mercurial's built-in web server obfuscates email addresses, to make it more difficult for the email harvesting tools that spammers use. This reduces the likelihood that you'll start receiving more junk email if you publish a Mercurial repository on the web.

Getting started¶

The Mercurial command-line interface can be used by calling the command hg. The symbol for the chemical element Mercury is Hg, so this only seems

fitting.

To begin, we'll use the hg version command to find out whether Mercurial is installed properly. This allows us to view what Mercurial version we are using, but also

whether we've actually properly installed Mercurial and can use its command-line interface.

$ hg version

Mercurial Distributed SCM (version 4.2)

(see https://mercurial-scm.org for more information)

Copyright (C) 2005-2017 Matt Mackall and others

This is free software; see the source for copying conditions. There is NO

warranty; not even for MERCHANTABILITY or FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE.

Built-in help¶

Mercurial provides a built-in help system. This is invaluable for those times when you find yourself stuck trying to remember how to run a command. If

you are completely stuck, simply run hg help; it will print a brief list of commands, along with a description of what each does. If you ask for help on a specific command (as

below), it prints more detailed information.

$ hg help init

hg init [-e CMD] [--remotecmd CMD] [DEST]

create a new repository in the given directory

Initialize a new repository in the given directory. If the given directory

does not exist, it will be created.

If no directory is given, the current directory is used.

It is possible to specify an "ssh://" URL as the destination. See 'hg help

urls' for more information.

Returns 0 on success.

options:

-e --ssh CMD specify ssh command to use

--remotecmd CMD specify hg command to run on the remote side

--insecure do not verify server certificate (ignoring web.cacerts

config)

(some details hidden, use --verbose to show complete help)

For a more impressive level of detail (which you won't usually need) run hg help. The -v option is short for --verbose, and tells

Mercurial to print more information than it usually would.

There are a few more options in the help system. For example, using the -k or --keyword option, you can search through the help system for a

specific word.

$ hg help -k init

Topics:

config Configuration Files

glossary Glossary

merge-tools Merge Tools

revisions Specifying Revisions

templating Template Usage

Commands:

init create a new repository in the given directory

paths show aliases for remote repositories

Working with a repository¶

In Mercurial, everything happens inside a repository. The repository for a project contains all of the files that “belong to” that project, along with a historical record of the project's files.

There's nothing particularly magical about a repository; it is simply a directory tree in your filesystem that Mercurial treats as special. You can rename or delete a repository any time you like, using either the command line or your file browser.

There are two major types of Mercurial commands:

- The first type allows you to work on a local repository, doing a number of actions on your own. These commands are purely local commands.

- The second type are network operations. These allow you to send changes to your code to another repository, or retrieve new changes from somebody else.

We will start our overview of Mercurial by looking at how you can use Mercurial on your own repository and expand into the network later on.

Creating your own repository¶

Creating a repository is quite simple. We can use the hg init command to create a new directory, which will be our repository.

$ hg init myproject

This simply creates a repository named myproject in the current directory.

$ ls -l

total 12

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 47 May 17 04:01 goodbye.c

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 45 May 17 04:01 hello.c

drwxr-xr-x 3 root root 4096 May 17 04:01 myproject

What's in a repository?¶

When we take a more detailed look inside a repository, we can see that it contains a directory named .hg. This is where Mercurial keeps all of its

metadata for the repository.

$ ls -al myproject

total 12

drwxr-xr-x 3 root root 4096 May 17 04:01 .

drwxr-xr-x 3 root root 4096 May 17 04:01 ..

drwxr-xr-x 3 root root 4096 May 17 04:01 .hg

The contents of the .hg directory and its subdirectories are private to Mercurial. Every other file and directory in the repository is yours to do

with as you please.

To introduce a little terminology, the .hg directory is the “real” repository, and all of the files and directories that coexist with it are said

to live in the working directory. An easy way to remember the distinction is that the repository contains the history of your project, while the

working directory contains a snapshot of your project at a particular point in history.

Adding content to the repository¶

We currently have a repository that contains no files in its working directory. Suppose we add a basic file to our working directory.

# ... edit edit edit ...

$ cat hello.c

int main()

{

printf("hello world!\n");

}

Mercurial's hg status command gives us a simple overview of the changed and unknown files in the working directory.

$ hg status

? hello.c

In our case, we've created a new file, but we haven't informed Mercurial about it yet. Since Mercurial doesn't know anything about this file, it's displayed with a question mark beside it. The file is currently an 'untracked file'.

We can inform Mercurial that we wish to start tracking our newly created file, by using hg add.

$ hg add hello.c

Now that our file has been added, we can see that Mercurial treats it differently.

$ hg status

A hello.c

It's somewhat helpful to know that we've modified hello.c, but we might prefer to know exactly what changes we've made to it. To do this, we use

the hg diff command.

$ hg diff

diff -r 000000000000 hello.c

--- /dev/null Thu Jan 01 00:00:00 1970 +0000

+++ b/hello.c Wed May 17 04:01:38 2017 +0000

@@ -0,0 +1,4 @@

+int main()

+{

+ printf("hello world!\n");

+}

Once we have a file (or multiple) that's being tracked by Mercurial, we can add it to our history. In Mercurial terminology, we call each stored 'snapshot' of history a changeset, because it can contain a record of changes to several files.

We can create a changeset ourselves, adding our new file permanently to the history of our repository. We can use the hg commit command for this

purpose. The process of creating a changeset is usually called "making a commit" or "committing".

The hg status command already showed us earlier what will happen when we make a commit. The 'A' next to our new file specifies that our file will

be added to the history.

$ hg commit -m 'Initial commit'

Now that we've committed our changes, we will no longer see them in the output of hg status. That makes sense: we usually only want to see the

files we're currently changing. It's possible to view other things as well, though, and we'll go into more detail about that later.

Let's change one more thing in our repository: the contents of our file aren't quite right. What happens if we change our file?

# ... edit edit edit ...

$ cat hello.c

int main()

{

printf("goodbye world!\n");

}

Again, we can use the status and diff commands to investigate what has changed in the repository.

$ hg status

M hello.c

$ hg diff

diff -r 9d16f03a559f hello.c

--- a/hello.c Thu Jan 01 00:00:00 1970 +0000

+++ b/hello.c Wed May 17 04:01:38 2017 +0000

@@ -1,4 +1,4 @@

int main()

{

- printf("hello world!\n");

+ printf("goodbye world!\n");

}

The “M” indicates that Mercurial has noticed that we modified hello.c. We didn't need to inform Mercurial that we were going to modify the

file before we started, or that we had modified the file after we were done; it was able to figure this out itself.

Once a file has been added to a repository, Mercurial will see any changes we make to it. There's no need to take any special action before

committing: hg commit will save the modifications into a changeset.

Besides status and diff, the hg summary command also allows us to quickly see what is going on in our working directory.

$ hg summary

parent: 0:9d16f03a559f tip

Initial commit

branch: default

commit: 1 modified

update: (current)

phases: 1 draft

We can see from the summary what changeset our working directory is based on and that a file has been modified. The summary contains some other information we haven't encountered yet, we'll go into those items later on.

Making a local copy of a repository¶

Copying a repository is just a little bit special. While you could use a normal file copying command to make a copy of a repository, it's best to

use a built-in command that Mercurial provides. This command is called hg clone, because it makes an identical copy of an existing repository.

$ hg clone https://bitbucket.org/bos/hg-tutorial-hello hello

requesting all changes

adding changesets

adding manifests

adding file changes

added 5 changesets with 5 changes to 2 files

updating to branch default

2 files updated, 0 files merged, 0 files removed, 0 files unresolved

One advantage of using hg clone is that, as we can see above, it lets us clone repositories over the network. Another is that it remembers where we cloned from, which

we'll find useful soon when we want to fetch new changes from another repository.

If our clone succeeded, we should now have a local directory called hello. This directory will contain some files.

$ ls -l

total 4

drwxr-xr-x 3 root root 4096 May 17 04:01 hello

$ ls hello

Makefile

hello.c

These files have the same contents and history in our repository as they do in the repository we cloned.

Every Mercurial repository is complete, self-contained, and independent. It contains its own private copy of a project's files and history. As we just mentioned, a cloned repository remembers the location of the repository it was cloned from, but Mercurial will not communicate with that repository, or any other, unless you tell it to.

What this means for now is that we're free to experiment with our repository, safe in the knowledge that it's a private “sandbox” that won't affect anyone else.

The first thing we'll do is isolate our experiment in a repository of its own. We use the hg clone command, but we don't need to clone a copy of the remote repository. Since we already have a copy of it locally, we can just clone that

instead. This is much faster than cloning over the network, and cloning a local repository uses less disk space in most cases, too [1].

$ cd ..

$ hg clone hello my-hello

updating to branch default

2 files updated, 0 files merged, 0 files removed, 0 files unresolved

$ cd my-hello

As an aside, it's often good practice to keep a “pristine” copy of a remote repository around, which you can then make temporary clones of to create sandboxes for each task you want to work on. This lets you work on multiple tasks in parallel, each isolated from the others until it's complete and you're ready to integrate it back. Because local clones are so cheap, there's almost no overhead to cloning and destroying repositories whenever you want.

When we make changes, we don't have any impact on the repository we cloned. We can safely add a line to the local file hello.c:

$ hg diff

diff -r 2278160e78d4 hello.c

--- a/hello.c Sat Aug 16 22:16:53 2008 +0200

+++ b/hello.c Wed May 17 04:01:29 2017 +0000

@@ -8,5 +8,6 @@

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

printf("hello, world!\");

+ printf("hello again!\n");

return 0;

}

A tour through history¶

One of the first things we might want to do with a new, unfamiliar repository is understand its history. The hg log command gives us a view of the

history of changes in the repository.

$ hg log

changeset: 4:2278160e78d4

tag: tip

user: Bryan O'Sullivan <bos@serpentine.com>

date: Sat Aug 16 22:16:53 2008 +0200

summary: Trim comments.

changeset: 3:0272e0d5a517

user: Bryan O'Sullivan <bos@serpentine.com>

date: Sat Aug 16 22:08:02 2008 +0200

summary: Get make to generate the final binary from a .o file.

changeset: 2:fef857204a0c

user: Bryan O'Sullivan <bos@serpentine.com>

date: Sat Aug 16 22:05:04 2008 +0200

summary: Introduce a typo into hello.c.

changeset: 1:82e55d328c8c

user: mpm@selenic.com

date: Fri Aug 26 01:21:28 2005 -0700

summary: Create a makefile

changeset: 0:0a04b987be5a

user: mpm@selenic.com

date: Fri Aug 26 01:20:50 2005 -0700

summary: Create a standard "hello, world" program

By default, this command prints a brief paragraph of output for each change to the project that was recorded. In Mercurial terminology, we call each of these recorded events a changeset, because it can contain a record of changes to several files.

The fields in a record of output from hg log are as follows.

changeset: This field has the format of a number, followed by a colon, followed by a hexadecimal (or hex) string. These are identifiers for the changeset. The hex string is a unique identifier: the same hex string will always refer to the same changeset in every copy of this repository. The number is shorter and easier to type than the hex string, but it isn't unique: the same number in two different clones of a repository may identify different changesets.user: The identity of the person who created the changeset. This is a free-form field, but it most often contains a person's name and email address.date: The date and time on which the changeset was created, and the timezone in which it was created. (The date and time are local to that timezone; they display what time and date it was for the person who created the changeset.)summary: The first line of the text message that the creator of the changeset entered to describe the changeset.- Some changesets, such as the first in the list above, have a

tagfield. A tag is another way to identify a changeset, by giving it an easy-to-remember name. (The tag namedtipis special: it always refers to the newest change in a repository.)

The default output printed by hg log is purely a summary; it is missing a lot of detail.

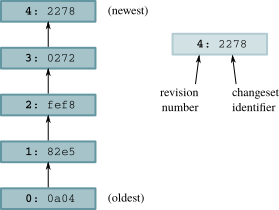

fig:tour-basic:history provides a graphical representation of the history of the hello repository, to make it a little easier to see which

direction history is “flowing” in. We'll be returning to this figure several times in this chapter and the chapter that follows.

Graphical history of the hello repository

Changesets, revisions, and talking to other people¶

As English is a notoriously sloppy language, and computer science has a hallowed history of terminological confusion (why use one term when four will do?), revision control has a variety of words and phrases that mean the same thing. If you are talking about Mercurial history with other people, you will find that the word “changeset” is often compressed to “change” or (when written) “cset”, and sometimes a changeset is referred to as a “revision” or a “rev”.

While it doesn't matter what word you use to refer to the concept of “a changeset”, the identifier that you use to refer to “a specific

changeset” is of great importance. Recall that the changeset field in the output from hg log identifies a changeset using both a number and a hexadecimal string.

- The revision number is a handy notation that is only valid in that repository.

- The hexadecimal string is the permanent, unchanging identifier that will always identify that exact changeset in every copy of the repository.

This distinction is important. If you send someone an email talking about “revision 33”, there's a high likelihood that their revision 33 will not be

the same as yours. The reason for this is that a revision number depends on the order in which changes arrived in a repository, and there is no

guarantee that the same changes will happen in the same order in different repositories. Three changes a,b,c can easily appear in one repository

as 0,1,2, while in another as 0,2,1.

Mercurial uses revision numbers purely as a convenient shorthand. If you need to discuss a changeset with someone, or make a record of a changeset for some other reason (for example, in a bug report), use the hexadecimal identifier.

Viewing specific revisions¶

To narrow the output of hg log down to a single revision, use the -r (or --rev) option. You can use either a revision number or a hexadecimal identifier, and you

can provide as many revisions as you want.

$ hg log -r 3

changeset: 3:0272e0d5a517

user: Bryan O'Sullivan <bos@serpentine.com>

date: Sat Aug 16 22:08:02 2008 +0200

summary: Get make to generate the final binary from a .o file.

$ hg log -r 0272e0d5a517

changeset: 3:0272e0d5a517

user: Bryan O'Sullivan <bos@serpentine.com>

date: Sat Aug 16 22:08:02 2008 +0200

summary: Get make to generate the final binary from a .o file.

$ hg log -r 1 -r 4

changeset: 1:82e55d328c8c

user: mpm@selenic.com

date: Fri Aug 26 01:21:28 2005 -0700

summary: Create a makefile

changeset: 4:2278160e78d4

tag: tip

user: Bryan O'Sullivan <bos@serpentine.com>

date: Sat Aug 16 22:16:53 2008 +0200

summary: Trim comments.

If you want to see the history of several revisions without having to list each one, you can use range notation; this lets you express the idea “I

want all revisions between abc and def, inclusive”.

$ hg log -r 2:4

changeset: 2:fef857204a0c

user: Bryan O'Sullivan <bos@serpentine.com>

date: Sat Aug 16 22:05:04 2008 +0200

summary: Introduce a typo into hello.c.

changeset: 3:0272e0d5a517

user: Bryan O'Sullivan <bos@serpentine.com>

date: Sat Aug 16 22:08:02 2008 +0200

summary: Get make to generate the final binary from a .o file.

changeset: 4:2278160e78d4

tag: tip

user: Bryan O'Sullivan <bos@serpentine.com>

date: Sat Aug 16 22:16:53 2008 +0200

summary: Trim comments.

Mercurial also honours the order in which you specify revisions, so hg log -r 2:4 prints 2, 3, and 4. while hg log -r 4:2 prints 4, 3, and 2.

More detailed information¶

While the summary information printed by hg log is useful if you already know what you're looking for, you may need to see a complete description

of the change, or a list of the files changed, if you're trying to decide whether a changeset is the one you're looking for. The hg log command's

-v (or --verbose) option gives you this extra detail.

$ hg log -v -r 3

changeset: 3:0272e0d5a517

user: Bryan O'Sullivan <bos@serpentine.com>

date: Sat Aug 16 22:08:02 2008 +0200

files: Makefile

description:

Get make to generate the final binary from a .o file.

If you want to see both the description and content of a change, add the -p (or --patch) option. This displays the content of a change as a

unified diff.

$ hg log -v -p -r 2

changeset: 2:fef857204a0c

user: Bryan O'Sullivan <bos@serpentine.com>

date: Sat Aug 16 22:05:04 2008 +0200

files: hello.c

description:

Introduce a typo into hello.c.

diff -r 82e55d328c8c -r fef857204a0c hello.c

--- a/hello.c Fri Aug 26 01:21:28 2005 -0700

+++ b/hello.c Sat Aug 16 22:05:04 2008 +0200

@@ -11,6 +11,6 @@

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

- printf("hello, world!\n");

+ printf("hello, world!\");

return 0;

}

The -p option is tremendously useful, so it's well worth remembering.

All about command options¶

Let's take a brief break from exploring Mercurial commands to discuss a pattern in the way that they work; you may find this useful to keep in mind as we continue our tour.

Mercurial has a consistent and straightforward approach to dealing with the options that you can pass to commands. It follows the conventions for options that are common to modern Linux and Unix systems.

- Every option has a long name. For example, as we've already seen, the

hg logcommand accepts a--revoption. - Most options have short names, too. Instead of

--rev, we can use-r. (The reason that some options don't have short names is that the options in question are rarely used.) - Long options start with two dashes (e.g.

--rev), while short options start with one (e.g.-r). - Option naming and usage is consistent across commands. For example, every command that lets you specify a changeset ID or revision number accepts

both

-rand--revarguments. - If you are using short options, you can save typing by running them together. For example, the command

hg log -v -p -r 2can be written ashg log -vpr2.

In the examples throughout this book, I usually use short options instead of long. This simply reflects my own preference, so don't read anything significant into it.

Most commands that print output of some kind will print more output when passed a -v (or --verbose) option, and less when passed -q (or

--quiet).

Note

Almost always, Mercurial commands use consistent option names to refer to the same concepts. For instance, if a command deals with changesets,

you'll always identify them with --rev or -r. This consistent use of option names makes it easier to remember what options a particular

command takes.

Good commit practices¶

Writing a commit message¶

When we commit a change, Mercurial drops us into a text editor, to enter a message that will describe the modifications we've made in this changeset.

This is called the commit message. It will be a record for readers of what we did and why, and it will be printed by hg log after we've finished

committing.

$ hg commit

The editor that the hg commit command drops us into will contain an empty line or two, followed by a number of lines starting with “HG:”.

This is where I type my commit comment.

HG: Enter commit message. Lines beginning with 'HG:' are removed.

HG: --

HG: user: Bryan O'Sullivan <bos@serpentine.com>

HG: branch 'default'

HG: changed hello.c

Mercurial ignores the lines that start with “HG:”; it uses them only to tell us which files it's recording changes to. Modifying or deleting these

lines has no effect.

Writing a good commit message¶

Since hg log only prints the first line of a commit message by default, it's best to write a commit message whose first line stands alone. Here's

a real example of a commit message that doesn't follow this guideline, and hence has a summary that is not readable.

changeset: 73:584af0e231be

user: Censored Person <censored.person@example.org>

date: Tue Sep 26 21:37:07 2006 -0700

summary: include buildmeister/commondefs. Add exports.

As far as the remainder of the contents of the commit message are concerned, there are no hard-and-fast rules. Mercurial itself doesn't interpret or care about the contents of the commit message, though your project may have policies that dictate a certain kind of formatting.

My personal preference is for short, but informative, commit messages that tell me something that I can't figure out with a quick glance at the output

of hg log --patch.

If we run the hg commit command without any arguments, it records all of the changes we've made, as reported by hg status and hg diff.

Note

Like other Mercurial commands, if we don't supply explicit names to commit to the hg commit, it will operate across a repository's entire working directory. Be wary of this if you're coming from the Subversion or CVS

world, since you might expect it to operate only on the current directory that you happen to be visiting and its subdirectories.

Aborting a commit¶

If you decide that you don't want to commit while in the middle of editing a commit message, simply exit from your editor without saving the file that it's editing. This will cause nothing to happen to either the repository or the working directory.

Admiring our new handiwork¶

Once we've finished the commit, we can use the hg log --rev . command to display the changeset we just created. In this command, the '.' specifies

that we want to view the current changeset. In other words, it will show us what we just committed.

$ hg log -r . -vp

changeset: 5:3358452fd7d5

tag: tip

user: test

date: Thu Jan 01 00:00:00 1970 +0000

files: hello.c

description:

Added an extra line of output

diff -r 2278160e78d4 -r 3358452fd7d5 hello.c

--- a/hello.c Sat Aug 16 22:16:53 2008 +0200

+++ b/hello.c Thu Jan 01 00:00:00 1970 +0000

@@ -8,5 +8,6 @@

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

printf("hello, world!\");

+ printf("hello again!\n");

return 0;

}

Sharing changes¶

We mentioned earlier that repositories in Mercurial are self-contained. This means that the changeset we just created exists only in our my-hello

repository. Let's look at a few ways that we can propagate this change into other repositories.

Pulling changes from another repository¶

To get started, let's clone our original hello repository, which does not contain the change we just committed. We'll call our temporary

repository hello-pull.

$ cd ..

$ hg clone hello hello-pull

updating to branch default

2 files updated, 0 files merged, 0 files removed, 0 files unresolved

We'll use the hg pull command to bring changes from my-hello into hello-pull. However, blindly pulling unknown changes into a repository is a somewhat

scary prospect. Mercurial provides the hg incoming command to tell us what changes the hg pull command would pull into the repository, without actually pulling the changes in.

$ cd hello-pull

$ hg incoming ../my-hello

comparing with ../my-hello

searching for changes

changeset: 5:3358452fd7d5

tag: tip

user: test

date: Thu Jan 01 00:00:00 1970 +0000

summary: Added an extra line of output

Bringing changes into a repository is a simple matter of running the hg pull command, and optionally telling it which repository to pull from.

$ hg log --limit 3

changeset: 4:2278160e78d4

tag: tip

user: Bryan O'Sullivan <bos@serpentine.com>

date: Sat Aug 16 22:16:53 2008 +0200

summary: Trim comments.

changeset: 3:0272e0d5a517

user: Bryan O'Sullivan <bos@serpentine.com>

date: Sat Aug 16 22:08:02 2008 +0200

summary: Get make to generate the final binary from a .o file.

changeset: 2:fef857204a0c

user: Bryan O'Sullivan <bos@serpentine.com>

date: Sat Aug 16 22:05:04 2008 +0200

summary: Introduce a typo into hello.c.

$ hg pull ../my-hello

pulling from ../my-hello

searching for changes

adding changesets

adding manifests

adding file changes

added 1 changesets with 1 changes to 1 files

(run 'hg update' to get a working copy)

$ hg log --limit 3

changeset: 5:3358452fd7d5

tag: tip

user: test

date: Thu Jan 01 00:00:00 1970 +0000

summary: Added an extra line of output

changeset: 4:2278160e78d4

user: Bryan O'Sullivan <bos@serpentine.com>

date: Sat Aug 16 22:16:53 2008 +0200

summary: Trim comments.

changeset: 3:0272e0d5a517

user: Bryan O'Sullivan <bos@serpentine.com>

date: Sat Aug 16 22:08:02 2008 +0200

summary: Get make to generate the final binary from a .o file.

As you can see from the before-and-after output, we have successfully pulled changes into our repository. However, Mercurial separates pulling changes in from updating the working directory. There remains one step before we will see the changes that we just pulled appear in the working directory.

Tip

It is possible that due to the delay between running hg incoming and hg pull, you may not see all changesets that will be brought from the

other repository. Suppose you're pulling changes from a repository on the network somewhere. While you are looking at the hg incoming output,

and before you pull those changes, someone might have committed something in the remote repository. This means that it's possible to pull more

changes than you saw when using hg incoming.

If you only want to pull precisely the changes that were listed by hg incoming, or you have some other reason to pull a subset of changes,

simply identify the change that you want to pull by its changeset ID, e.g. hg pull -r7e95bb.

Updating the working directory¶

We have so far glossed over the relationship between a repository and its working directory. The hg pull command that we ran in

sec:tour:pull brought changes into the repository, but if we check, there's no sign of those changes in the working directory. This is because

hg pull does not (by default) touch the working directory. Instead, we use the hg update command to do this.

$ grep printf hello.c

printf("hello, world!\");

$ hg update

1 files updated, 0 files merged, 0 files removed, 0 files unresolved

$ grep printf hello.c

printf("hello, world!\");

printf("hello again!\n");

It might seem a bit strange that hg pull doesn't update the working directory automatically. There's actually a good reason for this: you can use

hg update to update the working directory to the state it was in at any revision in the history of the repository. If you had the working

directory updated to an old revision—to hunt down the origin of a bug, say—and ran a hg pull which automatically updated the working

directory to a new revision, you might not be terribly happy.

Since pull-then-update is such a common sequence of operations, Mercurial lets you combine the two by passing the -u option to hg pull.

If you look back at the output of hg pull in sec:tour:pull when we ran it without -u, you can see that it printed a helpful reminder

that we'd have to take an explicit step to update the working directory.

To find out what revision the working directory is at, use the hg parents command.

$ hg parents

changeset: 5:3358452fd7d5

tag: tip

user: test

date: Thu Jan 01 00:00:00 1970 +0000

summary: Added an extra line of output

If you look back at fig:tour-basic:history, you'll see arrows connecting each changeset. The node that the arrow leads from in each case is a parent, and the node that the arrow leads to is its child. The working directory has a parent in just the same way; this is the changeset that the working directory currently contains.

To update the working directory to a particular revision, give a revision number or changeset ID to the hg update command.

$ hg update 2

2 files updated, 0 files merged, 0 files removed, 0 files unresolved

$ hg parents

changeset: 2:fef857204a0c

user: Bryan O'Sullivan <bos@serpentine.com>

date: Sat Aug 16 22:05:04 2008 +0200

summary: Introduce a typo into hello.c.

$ hg update

2 files updated, 0 files merged, 0 files removed, 0 files unresolved

$ hg parents

changeset: 5:3358452fd7d5

tag: tip

user: test

date: Thu Jan 01 00:00:00 1970 +0000

summary: Added an extra line of output

If you omit an explicit revision, hg update will update to the tip revision, as shown by the second call to hg update in the example above.

Pushing changes to another repository¶

Mercurial lets us push changes to another repository, from the repository we're currently visiting. As with the example of hg pull above, we'll

create a temporary repository to push our changes into.

$ cd ..

$ hg clone hello hello-push

updating to branch default

2 files updated, 0 files merged, 0 files removed, 0 files unresolved

The hg outgoing command tells us what changes would be pushed into another repository.

$ cd my-hello

$ hg outgoing ../hello-push

comparing with ../hello-push

searching for changes

changeset: 5:3358452fd7d5

tag: tip

user: test

date: Thu Jan 01 00:00:00 1970 +0000

summary: Added an extra line of output

And the hg push command does the actual push.

$ hg push ../hello-push

pushing to ../hello-push

searching for changes

adding changesets

adding manifests

adding file changes

added 1 changesets with 1 changes to 1 files

As with hg pull, the hg push command does not update the working directory in the repository that it's pushing changes into. Unlike hg pull, hg push does not provide a -u option that updates the other repository's working directory. This asymmetry is deliberate: the repository

we're pushing to might be on a remote server and shared between several people. If we were to update its working directory while someone was working

in it, their work would be disrupted.

What happens if we try to pull or push changes and the receiving repository already has those changes? Nothing too exciting.

$ hg push ../hello-push

pushing to ../hello-push

searching for changes

no changes found

Default locations¶

When we clone a repository, Mercurial records the location of the repository we cloned in the .hg/hgrc file of the new repository. If we don't

supply a location to hg pull from or hg push to, those commands will use this location as a default. The hg incoming and hg outgoing

commands do so too.

If you open a repository's .hg/hgrc file in a text editor, you will see contents like the following.

[paths]

default = http://www.selenic.com/repo/hg

It is possible—and often useful—to have the default location for hg push and hg outgoing be different from those for hg pull and

hg incoming. We can do this by adding a default-push entry to the [paths] section of the .hg/hgrc file, as follows.

[paths]

default = http://www.selenic.com/repo/hg

default-push = http://hg.example.com/hg

Sharing changes over a network¶

The commands we have covered in the previous few sections are not limited to working with local repositories. Each works in exactly the same fashion over a network connection; simply pass in a URL instead of a local path.

$ hg outgoing https://bitbucket.org/bos/hg-tutorial-hello

comparing with https://bitbucket.org/bos/hg-tutorial-hello

searching for changes

changeset: 5:3358452fd7d5

tag: tip

user: test

date: Thu Jan 01 00:00:00 1970 +0000

summary: Added an extra line of output

In this example, we can see what changes we could push to the remote repository, but the repository is understandably not set up to let anonymous users push to it.

Conclusion¶

It takes just a few moments to start using Mercurial on a new project, which is part of its appeal. Revision control is now so easy to work with, we can use it on the smallest of projects that we might not have considered with a more complicated tool.

| [1] | The saving of space arises when source and destination repositories are on the same filesystem, in which case Mercurial will use hardlinks to do copy-on-write sharing of its internal metadata. If that explanation meant nothing to you, don't worry: everything happens transparently and automatically, and you don't need to understand it. |